May 2022

A groundbreaking new study on the Black-white wealth gap in the U.S. shows that progress on closing the gap has all but stalled since the 1950s and inequality is on track to grow moving forward.

The study by Princeton’s Ellora Derenoncourt and the University of Bonn’s Chi Hyun Kim, Moritz Kuhn, and Moritz Schularick was made possible by a major effort to build an extensive new dataset that includes previously unavailable data on Black wealth from the time immediately after Emancipation until now.

The analysis of this new data not only reveals an alarming portrait of racial wealth disparities that exist to this day, but allows the researchers to examine what factors have led to these persisting inequities. They find Black individuals and white individuals experienced very different rates of increased savings and returns on wealth over the last 150 years. In recent years, large gaps in capital gains earnings between white individuals and Black individuals have been an especially big driver of the gap.

“Current patterns suggest that we have, for the first time in decades, left the convergence path altogether. Today, the Black-white wealth gap is growing, not getting smaller,” said Ellora Derenoncourt, Assistant Professor of Economics and Director of Princeton’s Program for Research on Inequality.

New data on Black wealth from 1860 to today

Most surveys of wealth with information on racial identity begin in the 1980s. The authors fill in 100 years of missing data on Black wealth by digitizing 50 years of southern state tax returns (from the 1860s to the 1910s) and combining that data with digitized Census data from 1860 and 1870. From there, they use an estimator to extend their data through the mid-19th century, verifying the accuracy of the results by comparing them to available data from the 1930s. Finally, they complete their time-series on Black wealth from the mid-20th century to today by using Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) data.

To aid further study on racial wealth gaps, the authors have made this important new dataset publicly available to other researchers.

The gap was closing–and then it wasn’t

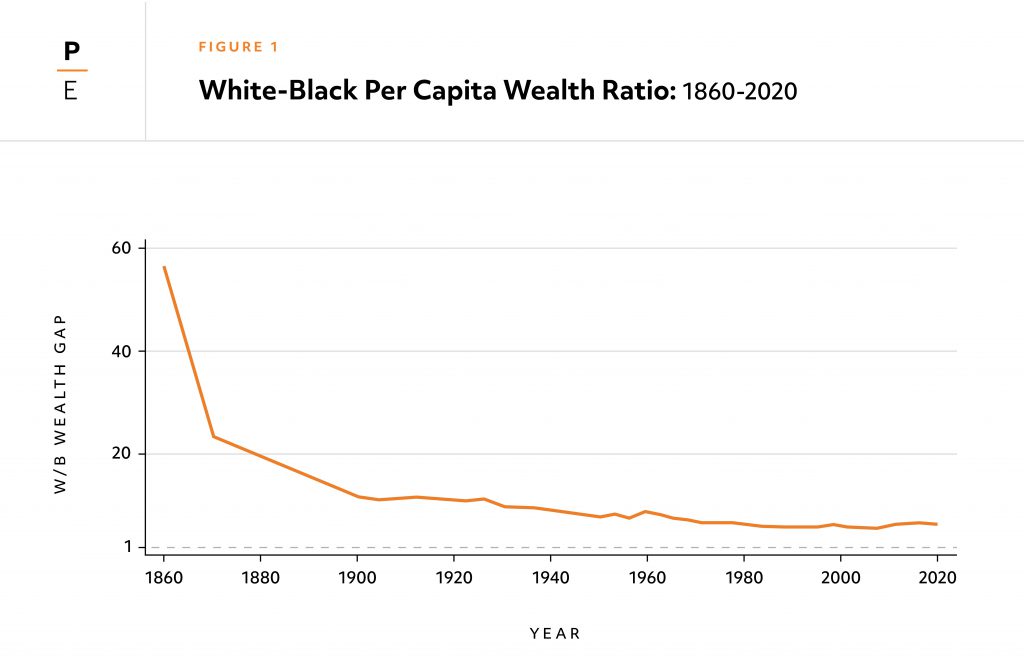

Immediately after Emancipation, the white to Black racial wealth gap in the U.S. was nearly 60 to 1. By 1920, it was 10 to 1, and by 1950 it was 7 to 1. Today–more than seventy years later–it remains at 6 to 1.

If Black and white individuals had identical savings and capital gains rates over time–which the research shows they did not–the racial wealth gap today would be about 3 to 1. Simply put, the gap was so large post-Emancipation that even equal earnings and savings rates between Black and white individuals would have resulted in a wealth gap that, though half what it is today, would have Black individuals holding about 30 cents for every $1 held by white individuals.

In order to identify periods of sluggish versus more rapid convergence, the researchers compare how quickly the gap actually closed to how quickly it would have closed if Black and white individuals had equal savings rates.

Despite the progress in racial wealth convergence in the decades after Emancipation, the researchers show that the gap shrunk slower in this period (1870-1930) than would be expected if Black and white Americans had enjoyed equal savings and capital gains. This suggests factors like discrimination and segregation played a role in suppressing possible progress in racial wealth convergence during these critical decades after slavery.

There is only one period where the gap closed more quickly than would be expected under an equal savings rate and capital gains scenario: The period during and just after the civil rights movement, from the 1960s to the 1980s.

“This is a really important observation from the data, because it suggests that the Black activism that led to civil rights legislation, a larger social safety net, and better labor standards may have given an extra boost to Black wealth accumulation,” said Derenoncourt.

Since the 1980s, progress on closing the gap has stalled, and the research shows that large differences in wealth-to-income ratios and investment portfolios between Black and white individuals have played a major role.

“For example, Black households hold nearly two thirds of their wealth in housing and very little in equity,” the authors write. “While housing wealth has appreciated since 1950, stock equity has appreciated by five times as much. These large price increases in equity markets have led to disproportionate capital gains for the wealthiest Americans, a group that is almost exclusively white.”

Policies to address the Black-white wealth gap

The authors write that their findings cast a spotlight on the fact that today’s Black-white wealth gap is a direct legacy of slavery and the discriminatory institutions that followed it–and likely wouldn’t have entirely closed even with policies that reduced inequities in investment returns and savings among Black and white Americans.

Policies that target unequal returns on wealth or savings rates can help close the racial wealth gap, they say, but it could still take several hundred more years for Black wealth to match white wealth.

“In light of these findings, we conclude that policies that redistribute large stocks of wealth, like reparations, lead to immediate reductions in racial wealth inequality while policies targeting portfolio composition can return us to a convergence path, but one that could take hundreds of years to play out,” they write. “Nevertheless, we argue these approaches are complementary, as policies that redistribute stocks of wealth without addressing racial gaps in savings and capital gains have but a transient effect on the wealth gap.”